A poetic essay on analog intelligence, artistic presence, and the grief of creating for algorithms instead of connection.

Maybe you’ve noticed it too. A quiet return to film. Not just the look of it—but the feeling. Grain. Softness. Something slightly out of focus that somehow feels more honest. This trend’s been bubbling in the wedding world for years now, but lately, I’ve noticed it trickling into food photography too. And I think there’s something deeper going on than just visual preference.

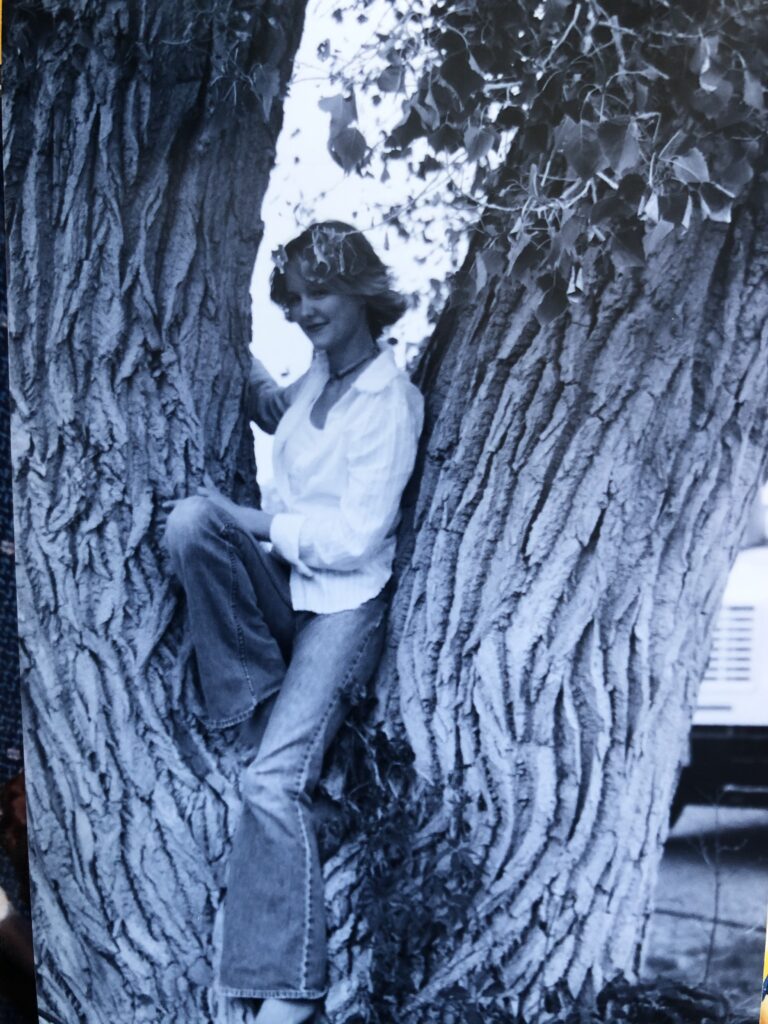

Secret time: I started on film.

I learned photography in the era of film. Digital cameras were just starting to be available. I carried around a film camera in college and once a week, I’d drop the roll off at the local pharmacy—marking the order slip so the photos would come back matte with a white border. That white border made them feel alive. More professional. Like something important.

Waiting to get those envelopes back felt like Christmas. Some shots turned out amazing—little treasures I’ll keep forever. Others came back too blurry, too dark. Total mystery captures. But that surprise? That thrill of not knowing? I was addicted. To the anticipation, the tangibility, the imperfections.

Why are so many couples asking for film again?

I think it comes down to three reasons:

1. Because it slows things down.

Film forces presence. It asks the photographer to wait, to frame with care. There’s reverence in that pause—a quiet honoring of the moment.

2. Because it creates an heirloom.

Film ages with us. It yellows, curls, becomes part of the family’s mythology. Digital files are endless. But film is real. Physical. Time-worn. Loved.

3. Because it doesn’t just look different—it feels different.

It’s not just grain or softness. It’s the imperfection. The unrepeatability. The thing they’re chasing isn’t just a style—it’s a sensation. Even if they can’t put it into words.

They’re not just chasing a look… they’re chasing a feeling.

What does “analog” even mean, really?

We throw the word “analog” around a lot: film, records, typewriters, anything nostalgic. But technically?

- It comes from Greek: ana- (up, back, again) and logos (word, reason, ratio).

- Originally: analogon = “something comparable or proportionate.”

In tech terms, analog systems are continuous—like grooves on a vinyl record. In contrast, digital systems are discrete—ones and zeroes. Binary. Exact.

So in a broad sense: analog is physical, proportional, and natural. Digital is artificial, fragmented, and optimized.

We’re craving a return to the real.

And not just brides and grooms. Not just photographers. All of us.

Last week, copywriter Ann Handley introduced a phrase I can’t stop thinking about: Analog Intelligence. It’s been living rent-free in my mind ever since.

Because there’s a difference between analog as an aesthetic… and analog as a way of thinking. One is about how something looks. The other is about how something feels—how it slows us, grounds us, connects us to texture, time, memory.

And honestly? I think what we call nostalgia might actually be grief. A quiet kind of grief—for the attention and presence we’ve lost.

Millennials are the threshold generation.

We remember what it was like before we were always reachable.

We grew up between:

- Corded phones and DMs

- Passing notes and reading texts

- Disposable cameras and disappearing stories

- Memory-making and content-creating

We remember the taste of boredom. The weight of silence. The texture of a moment not yet shared. That memory is a gift—but also a grief.

The ache of being watched—and invisible.

This isn’t resistance to progress. I love social media. I love ChatGPT. But lately, I’ve realized how much of myself I’ve shaped around what I think will be liked.What will perform?

What will earn the next dopamine hit?

We live in a world where everything is made to be shared—quickly, perfectly, bite-sized. Where presence is secondary to performance.

And somewhere in all that optimizing, we lose track of where creativity used to come from. It didn’t come from marketing strategies. It came from instinct. Joy. Curiosity.

Now I look at something I’ve made—something technically good—and I feel… sad? Like it’s not mine anymore. Like it doesn’t have my fingerprints on it.

Some of it was made with joy. But a lot of it? Was made to please. To perform. And when something looks great but holds no meaning? It cheapens the whole thing. And that’s a kind of sadness I can’t ignore.

The algorithm is hungry. And it’s eating us.

We’re in a system that demands constant output—and offers no real nourishment in return. The slow erosion of joy. Of instinct. Of the why behind the work.

There’s a quote (often attributed to Bukowski):

“The tragedy of life is not death but what we let die inside of us while we live.”

We’re not creating from joy anymore. We’re creating for data.

1s. 0s. Reach. Clicks. Likes.

Ann Handley put it this way:

“We’ve made patience feel like a liability.”

And she’s right. In a world of reels and reach, slowness looks like failure.

But the problem runs deeper than pace.

When your style isn’t even yours anymore

Ru Kotryna wrote something that gutted me:

“There is a violence in over-design—the quiet erasure that happens when a space loses its echo. When light is no longer allowed to wander.”

We’ve mistaken the algorithm’s aesthetic for our own.

We don’t create to explore. We create to prove. And in all that proving, something sacred starts to vanish.

The question that no longer helps

People love to ask: “What would you make if no one was watching?” But that question doesn’t land anymore. Because now, everyone is watching—and no one is. The gaze is constant, but fleeting. The visibility is shallow, but exhausting. We live our lives half-paused for performance, half-forgotten by the scroll.

So we ask ourselves:

Is this mine?

Or is this a performance?

Is this joy?

Or is it proof?

I don’t want to make things just to feed the algorithm.

Instagram is just a starving beast with a taste for chicken nuggets.

And honestly? I’m aiming higher than nuggets.

We are analog.

Analog intelligence isn’t about abandoning tools.

It’s about remembering how to feel again.

It’s about:

- Material honesty over performance

- Resonance over reach

- Presence over polish

Ann Handley says:

“Analog habits help you notice. They sharpen discernment. They help you hear your own signal and trust yourself before you start asking others for theirs.”

Ru Kotryna says:

“What began as expression has quietly collapsed into an anxiety-inducing performance.”

And I say:

“We’ve left the deep wells of creativity to drink from potholes filled with stagnant rainwater. We’re not building anything real—we’re just playing dress-up. Just styling hollow corners of the internet. Just curating our grief.”

But here’s the thing:

We are not binary.

We are not exact.

We are the grooves on the record.

We are the scratches and the skips.

We age like photos.

We hold time in our skin.

We are analog.

So what now?

I don’t know the answer. But I know what I’m moving toward:

- Work that lets light wander.

- Stories that echo.

- Photos that feel.

- Slowness that honors the moment.

Because digital may dominate the feed—

But analog is what holds memory.

And memory, after all, is what makes anything truly real. And what is a good photo if not an actual memory preserved?

If this essay resonated, I’d love to hear from you. You can leave a comment below, share it on Instagram or LinkedIn, or send me a message and tell me what you’re creating that feels truly yours.

A Note to Readers

A Note to Readers

Yes—I used AI to help write this. A little ironic, right?

But I didn’t write this to reject our tools. I wrote it to reckon with how easily they reshape us if we’re not paying attention.

This piece wasn’t generated. It was gathered—from grief, from memory, from journal scraps and photo sessions and voice notes and late-night thoughts I didn’t know what to do with.

The AI helped me hold the thread.

But I pulled it through.

Because even in a world that rewards speed and surface, I still believe in the slow work. In language shaped by hand. In light that’s allowed to wander.

So yes, I used AI.

Like a mirror.

Like a second pen.

But the story—the ache—the voice?

It’s mine.

— Austin

Affiliate Information

As a part of the Amazon Affiliate program, I have the opportunity to share products and items that I genuinely find useful or interesting. When you come across links to these products on my blog, they're not just recommendations based on my personal experience or research; they also serve a dual purpose. If you decide to click on these links and make a purchase, I earn a small commission from Amazon at no additional cost to you.

This setup helps me to keep generating content that you find helpful and engaging, without bombarding you with irrelevant ads or sponsors. It's a win-win situation: you discover products that could add value to your life, and I get a little support to continue doing what I love. Rest assured, the integrity of my recommendations remains my top priority. I only share links to items that I believe in, and that I think could make a difference for you.

Thank you for your support and understanding. Your trust means the world to me, and I'm committed to maintaining transparency about how I fund my blog. If you have any questions about the Amazon Affiliate program or how it works, feel free to reach out.

©️ 2024 Now From Scratch | Template by Maya Palmer Designs | ©️ Photos by Austin Claire Photography| Privacy Policy | Terms